The Google AdTech Remedies Trial

Is there a monopoly issue in the AdTech stack, and if so, precisely what is it?

Many eyes in media, advertising and their technology partners are on Alexandria, Virginia for the second Google remedies trial - this time not on search but on AdTech. What exactly will the Court do with the advertising supply chain?

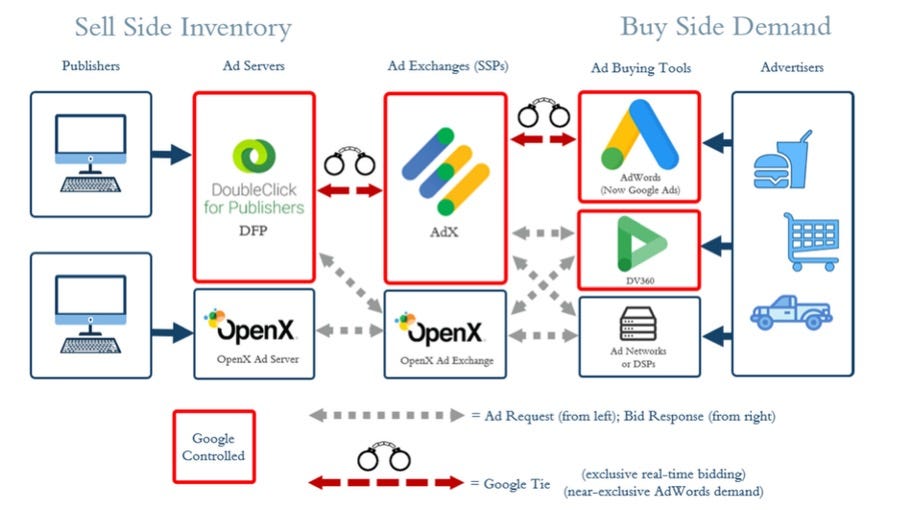

The underlying issue is that Judge Leonie Brinkema found an illegal tie by Google between the publisher-side ad server and the ad exchange, known respectively as DoubleClick for Publishers (DFP) and AdX. As a result, the court found monopolization of open web publisher-side advertising servers and open web display advertising exchanges.

A picture is worth a thousand words. The following schematic comes from OpenX’s August 4th complaint against Google in its related private lawsuit. It sets out the exact location of the allegations.

The underlying concern is that Google’s servers used by publishers (DoubleClick for Publishers or DFP above) could not easily be changed. The phrase “act of God” appears in the trial transcript. Google would only allow demand from its product for the middle, advertising exchange layer, known as AdX, to pass to its own publisher ad server (DFP). This came to be known as the “DFP-AdX tie.”

Importantly, Google is also present further up the supply chain in the servers used by advertisers. In particular, AdWords is a very strong client book of advertising demand. How exactly the case approaches the relationship between this AdWords layer of upstream demand, and the tying between the publisher server (DFP) and the exchange (AdX) may be the single most important question of all.

There, that wasn’t so bad was it, as dives into alphabet soup go?

There is much to note in the 115 page opinion. This note considers what the case didn’t say, and on that basis, what to watch at the remedies trial.

Oh, and if you are attending — see you there.

What the AdTech case did not do

The case rejects “big is bad” oversimplification

Google is big. Is that a bug or a feature? So much of the case pivots around this starting question.

There are more, and less, thoughtful approaches to the large scale of platforms. Platform scale can significantly enhance value for all involved by lowering average costs.

Widespread use of an ad exchange, whether AdX or alternatives, lowers average costs. The best outcome might well be large scale use of a platform, just at a competitive price point. The real competition question is therefore not scale or market share, but whether the benefits of scale are subject to competition.

It is therefore significant that the case refused to revisit the DoubleClick and Admeld acquisitions (pp.88-89). The DOJ alleged that these were anti-competitive purchases even though they were reviewed and cleared at the time.

Ultimately, Judge Brinkema declined to second guess those contemporaneous agency reviews, pointedly noting that the much-discussed DoubleClick approval was, in fact, a 4-1 vote for clearance. There was no appetite to second guess the expertise of the expert agencies, and the Judge shrewdly deferred to decisions made based on the facts of the time, rather than subsequent developments.

This focus point is of wide significance.

Many consumer-facing products have a history in which large firms buy small companies to scale up. Strikingly, YouTube operated above a San Mateo pizzeria before its purchase by Google. Contemporaneous press thought that the >$1bn payment was risky, whereas it now looks like a bargain. Android is another case of scale up of a relatively small company using the broad shoulders of a larger company.

This type of investment is critical for start ups and the argument that certain parties should not be able to do it just because they are large would harm investment and consumers. In scenarios where large firms do not have existing product lines, as was the case with YouTube and Android, it is important to allow them to enter and serve consumers. If that results in large scale operations from expansion, then large scale simply indicates success.

So, Judge Brinkema has fired a warning shot against retrospective analysis when there are plenty of current facts to address. Yes, the Clayton Act allows a lawsuit against a past acquisition – but is it wise to drive looking only into the rear-view mirror? Wisdom is knowing what not to challenge.

The reluctance to break scale for its own sake also aligns with the UK CMA’s decision pointedly to reject calls for Apple and Google to divest web browsers based on an asserted inherent conflict of interest, and the very recent rejection of structural remedies in the Google Search case.

The CMA’s reasoning is particularly noteworthy. The CMA threw out that possibility at a preliminary stage expressly on the basis that removing Apple from the market would amount to reducing competition and consumer choice. That is, even the platforms – perhaps, especially the platforms – can bring scale benefits to consumers.

This is not however to say that divestment is off the cards

The above points indicate reluctance to criticise scale. It does not mean, however, that scale will necessarily remain. Rather, the focus of the court will be on the current net economic costs and benefits of any divestment, implicitly including benefits to scale from large platform operations.

Strikingly, such an approach might well open up ties between products such as DFP and AdX – but it would not necessarily prevent presence at many levels of the supply chain, precisely because that is efficient. It is just that the large provider needs to compete openly with other options.

Importantly, that chimes with customer demand. Some publishers have gone public to say that they benefit from large scale operations across the supply chain. They would just like the Google supply to compete with other options across the supply chain by removing tying, especially at the higher level of AdWords demand into AdX.

Would the court really order a divestment over customer evidence saying that it benefits from scale? Stranger things have happened but it would perhaps puzzle some customers. From that perspective the real question is the quality of data interoperation and not the size of Google.

There is not very much analysis of the advertiser side of the market

For a case about online advertising, there is surprisingly little analysis of the advertiser side of the market at the remedies stage. This follows from the finding that a so-called relevant market for advertising networks had not been proven by the DOJ.

For antitrust lawyers, this a powerful reminder of the enduring importance of relevant market analysis. This is the requirement to prove the absence of reasonable materially constraining substitutes before an antitrust case can proceed. It is also much debated:

- Both generally as to whether the requirement is distracting from true competitive effects. The requirement may understate the impact on subgroups.

- And specifically as to whether technology markets move too quickly, or have too many adjacent markets, for relevant market proof to be apt.

Relevant markets must still be proven for US antitrust: proposed changes in the American Innovation and Choice Act never passed. So, the requirement to prove no materially constraining substitute remains.

The speed issue here may be particularly acute. Since the case, not only has AI grown, but there is increasing competition from connected television (CTV) advertising volumes.

Those types of wider dynamics proved difficult for the advertising part of the DOJ’s case. The DOJ faced difficulties from strong evidence that advertising consumers switch between open web and app based systems. There is a powerful example of competing use of Instagram. As the charge of an ad-side monopoly fell at the first hurdle, there is relatively little emphasis on the advertising side of the market.

As explored below, this has major implications for remedies.

There is not much analysis of the linkages between advertising and publishing

There is surprisingly little attention to the linkages between alleged market power on the publisher and advertiser sides of the market.

While there is certainly attention to the importance of AdWords demand to publishers (e.g., p.77-9), there is no direct analysis of the relationship between publishing and advertising demand.

Instead, there is a detailed discussion of the boundaries of the relevant appellate precedents. Most strikingly, Ohio et al. v American Express (‘AmEx’) looms large. This is the case by which the US Supreme Court required net analysis of both sides of a two-sided market, that is, those containing inter-linked demand such that total output may rise, or fall, differently across the whole market rather than just in part of it.

The point is a pivotal difference between US and EU antitrust, because EU antitrust allows (although does not mandate) the analysis to consider market power on one side of the market irrespective of total output dynamics. Whereas this would be an error in US antitrust if it effectively disapplies AmEx.

Judge Brinkema approached AmEx as, essentially, applicable to markets for transactions (p.61). In consequence, publisher side market power could raise issues despite competition on the advertising side of the market, because of the absence of a strong volumetric link between the two.

The logic of AmEx was applied impeccably to advertising networks (p.53): the question is to look across the whole of the market.

As regards publishing, there is a scenario in which market power in open web publishing systems could be monopolistic, despite alternatives on the advertising side.

It depends on the evidence and analysis.

However, when it came to the substance of the links between publisher and advertiser demand functions, there is not really a “full fat” analysis. Instead, there is an argument that AmEx differed. That is not the same thing as an analysis of this market and links within it.

This is potentially a significant oversight. It elides substitutes, complements and constraints even though these are different things.

Yes, there is a limitation to substitution for a publisher requiring open web demand – but there might still be constraint over supply to them because of competition in the adjacent advertising market. The observation that there is, or is not, close correlation (1:1) in transaction volumes says nothing in itself about competitive constraints, because the relative volumes of demand for product A and B can arise whether they are complements or substitutes, and whether or not there is a competitive constraint over them.

The court indulged in a bit of a “gotcha” here, rather than detailed analysis. This is temptation that might have been better avoided. At p.65, it is noted that Google had argued for a breakout of publisher from advertiser demand in a Californian class action defense. The issue here is that the current case ought to consider its own facts and not just the statements of defendants elsewhere.

Crediting the “gotcha” seems to have limited thoughtful analysis on the cross-market effects. Two critical points are understated in the judgment:

1. Linkages can still discipline competition between two sides of related markets even when the linkage is not 1:1. Just because there is no 1:1 relationship between the two sides, does not mean that competition in market A is irrelevant to market B.

2. An acute version of this oversight arises if rules in one of the two markets are required to improve competition overall. While the point is highly debatable, there are instances where total macro system use and output increases from micro competition restrictions.

Uniform Pricing Rules, price floors, and bidding density

There is much discussion of the Uniform Pricing Rules in the case. This closely relates to point (2) above: what should network rules be to address transaction costs across supply chains?

Uniform Pricing Rules as applied by Google were essentially a most-favored-nation or MFN clause requiring publishers not to set a floor price for AdX above the level of other exchanges. The court focused on the striking loss of price competition from this. Indeed, it prevented publishers from extracting the additional marginal value of AdX above the price of other exchanges – that was the point.

There is certainly precedent for concern about the impact of such clauses on pricing dynamics. This typically arises if a new entrant cannot cut price because of the need to apply the same discount to larger, incumbent volumes.

The counterargument is that MFNs prevent price rises. There is the very real possibility that such a clause could lower prices overall by preventing opportunistic increases of price within a supply chain. Indeed, it was none less than Judge Posner who said that it was “ingenious but perverse” to argue that MFNs, by setting limits to prices, could effectively raise them (Marshfield Clinic).

Here, the price decrease effect would arise if transaction costs prevent advertisers from achieving value on the publisher side of the market. In such a scenario, an exchange rule insisting on low prices might well increase advertiser demand, essentially by forbidding price discrimination by publishers as between different sources of demand for their content.

There is of course the thorny issue that publishers could equally be economically exploited if such a rule results in a price below the marginal value of content. And it is quite plausible that in some scenarios Ramsey pricing, that is, charging more for differing valuations of content, could induce extra output. After all, that has been a mainstay of publishing pricing ever since the first subscription model. It is why bidding density is debated and it is why there is a current debate over transaction ID forcing and its impact on bidding density.

Ultimately, setting price floors including by content pathway can help with dynamic bidding density strategies. Perhaps the point is not that floors should be abandoned, but that they should be customizable.

Good antitrust law here would not get involved in a commercial dispute between advertisers and publishers. Instead, the focus should be on whether competition is driving economically efficient activity in the relevant markets, considering the links between them.

In a perfect market, system rules would induce the efficient level of investment in content, advertisements, and the systems to connect them.

Ultimately, it is the interplay of the different parts of the market that generates total value. Seen in this way, whether looking from a publisher, AdTech, or advertiser perspective, there is no escaping the point that the optimal prices are products of demand from all sides of the market.

It is a significant limitation that this analysis was not materially undertaken. Instead, there is analysis of statements about margins in parts of the system, and the relatively narrow reading of Amex such that a 1:1 link is required for it to be engaged. Indeed, Google’s comment that there is “not 20% of value in connecting two bids” (p.79) came back to haunt it. But strictly that comment says nothing about the total system output.

As Google has already offered to stop UPRs this point may have to wait for the appeal rather than the remedies analysis.

Avoiding cases held together with Scotch tape

The relatively high-level approach to the thoughtful debates on scale and causation is most striking in the quick-fire treatment of three important cases on discounts in exchange for high sales volumes: 3M v. Lepage’s; Comcast v. Viacom, and Microsoft.

The most indicative is 3M. This is a well-known and somewhat lamented case on discounting. As part of a thicket of circuit splits on the role of discounting by firms with large shares, the precedent is all too familiar to antitrust advisors.

3M had engaged in discounting practices by which it gave larger discounts to those buying private label adhesive tape in addition to its branded Scotch tape. The reason the case is so discussed is that discounting is, ceteris paribus, good. That Lepage’s faced price competition is in itself a good thing. The case is a good example of why scale alone should not be the focus of analysis: if 3M gained share by lowering prices, that is not a bug but a feature of the conduct.

Against this backdrop, the venerable Supreme Court precedent in Brooke Group loomed large. Brooke Group by itself stands for the important proposition that sales above cost are not monopolistic in a pure price scenario, that is, one without attendant non-price conduct issues.

It will be interesting to see how exactly the court approaches the price vs non-price aspects of conduct, which is the heart of the circuit split, as regards remedies. Whether the remedy needs to exceed just stopping exclusivity depends on one’s reading of these cases. If this sounds familiar, that is because it is - it is the same point underlying the parsimony of the Google Search remedy.

What to watch

The remedies trial will provide an opportunity to revisit these themes from the April decision. All of them affect what a proportionate remedy ought to look like. Indeed, as we were recently reminded by Judge Mehta in the related Google Search case, remedies must link with some sort of reasonably close connection to the underlying theory of harm.

There, the DOJ had asked for perhaps a bit too much, and got perhaps a bit too little. This dynamic is very different for the AdTech case. The DOJ is much more focused on the underlying tie — the DFP-AdX tie — this time around.

The real question is where it arises. One more obscure point from the case to date is the role of market shares in the AdX exchange on a worldwide vs. US basis (pp.70-1 and p.83). The references to the underlying trial exhibits PTX1258-9 show that US shares are somewhat smaller than worldwide. Certainly, the DFP share is high. But is the AdX share really high enough to unbundle AdX and not just DFP under US antitrust law?

There is an argument that unbundling both AdX and DFP helps to address the two markets of concern. After all, it is the AdX market, and not the DFP market, which hosts the higher margin (c.20% - quite a bit for “comparing two bids.” (p.79)). By that logic some of the AdWords volume might need to interoperate with other exchanges. The case would not stop at just opening up the publisher side.

This, then, is the crux of the case. If the remedies trial were a set menu then the three items might be -

Open up DFP and AdX to competing other publisher servers by removing the publisher-side tie - Google’s proposal. Other publisher side servers could then handle the demand without the publisher losing the Google volume.

Go further and require the upstream AdWords demand to work with other ad exchanges, perhaps via a non-discrimination rule.

Use a divestment - Require Google to sell off the publisher ad server.

These are subtle points in a complex market. It will be interesting to see how the court approaches them. (2) is by far the most consequential. It is a little buried in the current debate but the first of the DOJ behavioral remedy proposals would effectively require Google and other demand to be treated the same across the bidding system.

Against this, Google will argue that it has built a customer book and mandating equivalence undermines that (listen out for the Trinko case). Publishers have argued that the demand should reflect the book building, and not any network rules, citing stricter cases on exclusivity (Lorain Journal).

As for me, I smile a little because the two points are related. Yes, Google built a formidable customer book on the ad side. But one reason is that a network was built to serve them. So the real question is whether the network rules are required to build total output. If that is so, then the network rules are helpful. But if the network rules reduced output then they are harmful. So the principled approach is to focus on network rules that will allow network growth over time - by Google and by its rivals.

Does that really mean that the network has to be the same for everyone’s traffic, or is it enough just for several network systems to compete?

That analysis would be much more fruitful than just arguing about what to sell in a messy divorce. Let’s see if the court features it starting Monday.